In November 2020 I wrote an essay titled “Risk”, exploring what risk means. As part of that essay, I briefly touched on the idea that useful predictions are impossible. Since then, I have continued to learn and think about decision-making under uncertainty.

I learned that to thrive in an uncertain world, we shouldn’t rely on making predictions; rather we should cultivate anti-fragility. Anti-fragility allows us to benefit from the stressful and unpredictable events life has in store.

This is what we will explore today. By the end of this essay, you will understand

- Why predictions are useless;

- What anti-fragility is;

- Why anti-fragility removes the need to make predictions; and

- Most importantly, principles for becoming anti-fragile so you can benefit from uncertainty.

The Absurdity of Certainty

There are two kinds of forecasters: those who don’t know, and those who don’t know they don’t know. – John Kenneth Galbraith

My disregard for predictions is because they are rarely helpful in making important decisions. This is for two reasons: 1) The only predictions that matter are outlier events (often called Black Swan events), and; 2) we don’t have a reliable process for predicting outlier events.

Outliers lead to outperformance

The purpose of predictions is to make decisions about the future that result in outperformance.

You will be wealthier if you can predict the next stock market crash. You will be safer if you can predict the next natural disaster. You will have the best tee times if you can predict the weather.

Outperformance requires non-consensus perspectives. It is not useful to predict what we expect to occur. If everyone thinks it will rain tomorrow, the golf course will be empty. If you disagree and are right, you will have the course to yourself.

Said another way, what we want to predict is outlier events.

Outlier events are non-consensus because they are random and rare events with profound impacts. Wars, stock market crashes, pandemics, terrorism attacks (e.g., September 11th), natural disasters, and new technological inventions (e.g., the internet and the car) are all examples of rare events with profound impacts.

Unreliable models

The issue is that predicting outlier events is impossible.

For a prediction to be reliable, there must be a process of converting inputs into outputs.

However, there isn’t a reliable process for turning all the variables associated with the future into an accurate prediction.

As an example, let’s look at one of the most common predictions: economic forecasts.

Think about all the inputs that surround this one prediction:

- What will the unemployment rate be?

- What will happen to commodity (e.g., oil) prices?

- Will geopolitical tensions lead to trade wars?

- What will the rate of innovation be?

- What will the central banks do? Will interest rates rise, fall, or stay constant?

- What will the rate of population growth be? What about immigration?

- What will the rate of productivity be?

- Which political party will be elected? What policies will they implement?

The point is that no one can balance all these factors to reach an accurate prediction of an outlier event. Doing so would require:

- Determining all the questions (inputs) that need to be answered, including inputs we haven’t yet considered (unknown unknowns)

- Coming up with answers to all the questions

- Considering the implications and interactions between all the inputs and how they influence each other

- Weighing the various inputs appropriately

- Synthesizing them into a non-consensus prediction

I can’t think of a more impossible task.

The turkey problem

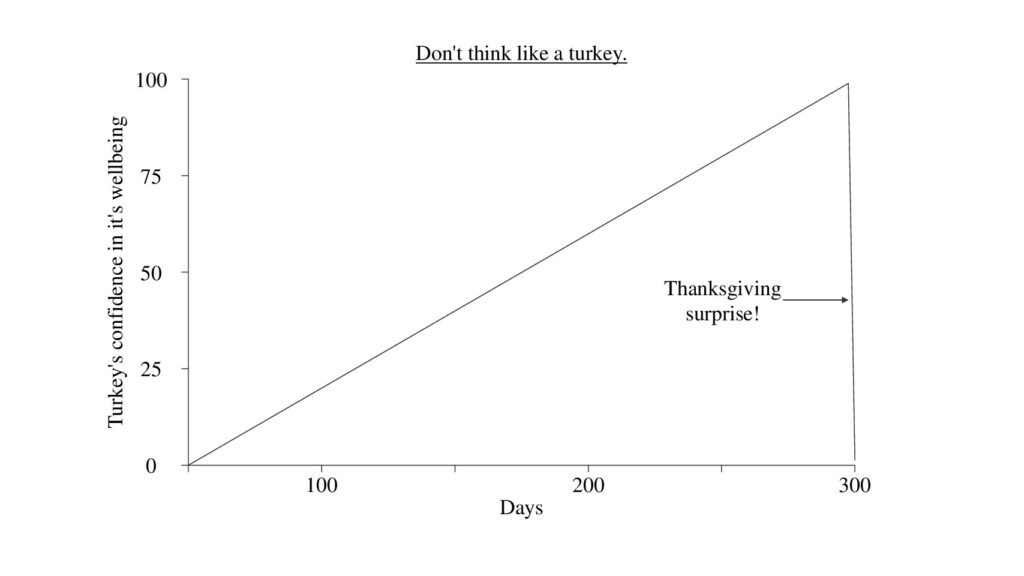

Imagine a turkey that is fed every day by a farmer.

Each passing day will increase the turkey’s confidence in the following statement: “Every day, I will be fed by a friendly farmer.”

However, on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, the turkey’s confidence in that statement will change.

The turkey problem should clearly highlight the two points below:

- What matters to the turkey is not predicting another “normal” day but, rather, predicting outlier events (e.g., Thanksgiving).

- Using historical inputs and data to make a prediction doesn’t work for outlier events. They are outlier events because people never thought they could happen. Consider this: The turkey’s confidence in its well-being was highest the day before Thanksgiving, when the risk was also the highest! It is catastrophic to rely on the past to predict what the future has in store.

Becoming the fire

Wind extinguishes a candle and energizes a fire – Nassim Taleb

You might point to rare instances in which people have predicted outlier events as evidence that it can be done. Michael Burry famously predicted the housing bubble in 2008 and a Hollywood movie was made about his prediction.

We can ignore this argument because it lacks reliability, a trait required for predictions. Michael Burry has made at least 10 other public stock market related predictions, all of them wrong, for a total record of 1/11. Even the smartest folks, like Mr. Burry, are not able to consistently predict outlier events. [1]

Regardless, it doesn’t matter whether you think that predictions are impossible or extremely difficult. There is a better way.

It is much easier to be anti-fragile than smart enough to predict the future.

The triad

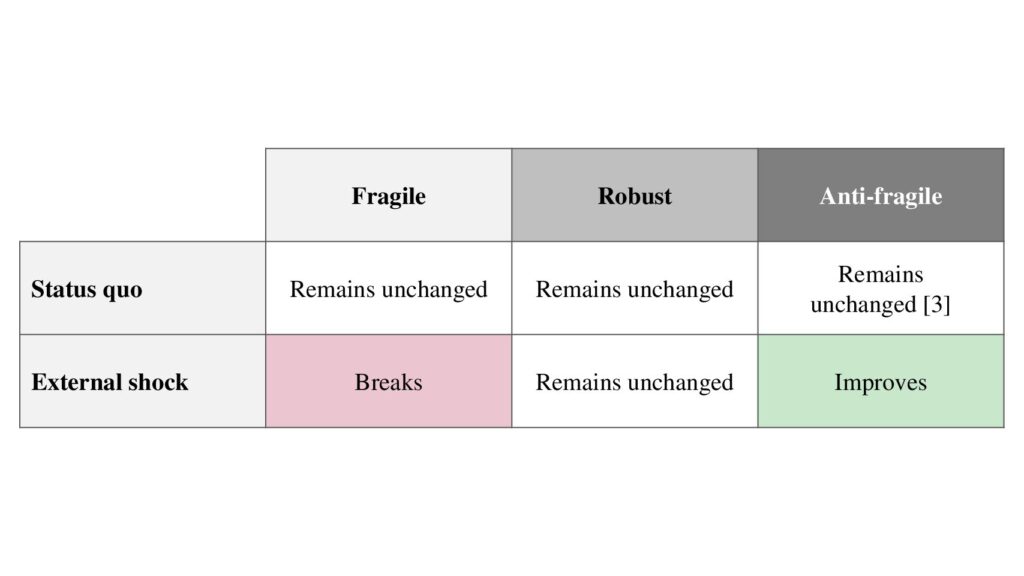

Everything in life is either fragile, robust, or anti-fragile.

Fragile things break when exposed to stressors. Robust things are resistant and absorb shocks. Anti-fragile things gain from stressors: They thrive and grow when exposed to outlier events.

Your glass cup falls from a kitchen table and, upon impact with the ground, breaks. Glass is fragile in this context.

You are Rollerblading in Central Park. Out of nowhere you hit a branch and crash. Your helmet hits the ground, protects your head, and doesn’t break. Your helmet is robust in this context. [2]

Your immune system is exposed to a new virus and, after a three-day battle, wins becoming stronger in the process. Your immune system is anti-fragile in this context.

Testing for positive asymmetry

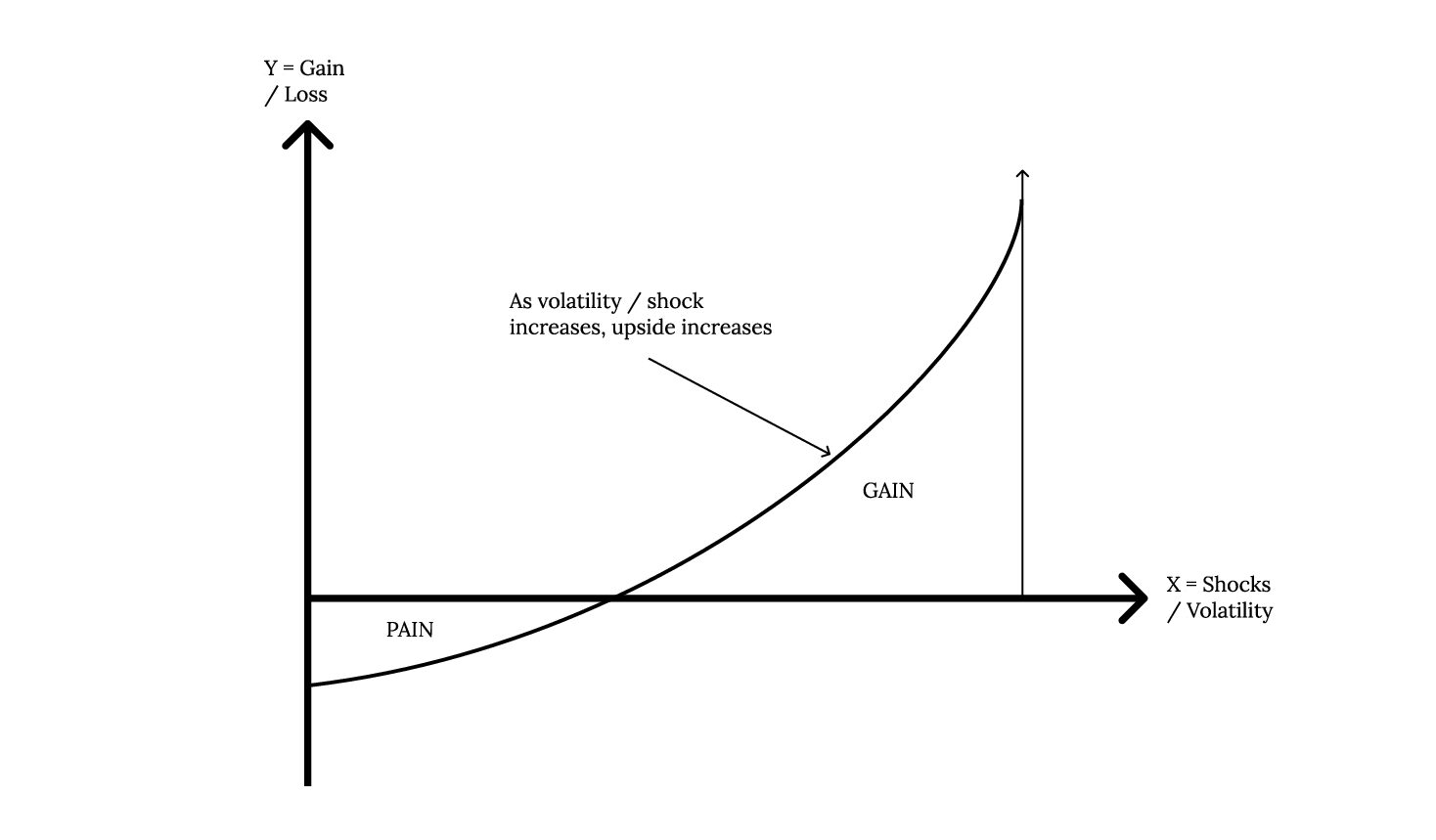

Looking at the table above, what should be clear is a test for anti-fragility. Anything that has a positive asymmetry (more upside than downside from shocks or outlier events) is anti-fragile.

There are numerous examples of things that are anti-fragile at different scales.

- Working out makes your body stronger. When exposed to external shock (weightlifting, running, etc.) your body is forced to overcompensate and adapt to meet similar future shocks.

- Wildfires make forests stronger. When a wildfire occurs, it removes the accumulation of combustible material and creates room for new wildlife. [3]

- Airlines are anti-fragile at the system level (although fragile at the airplane level). Each airplane crash results in improvement to the overall system (the totality of all airplanes) because of the identification of mistakes and process improvements.

Size matters

Before we run around seeking exposure to external shocks, it is important to realize that size matters.

The ability of a system, person, or thing to respond with anti-fragile characteristics to a stressor is dependent on the size of the stressor.

Small is better than large because harm is nonlinear. As the size of the shock increases, harm increases faster.

There is a difference between jumping 100 feet once and jumping one foot 100 times. One will kill you; the other will make your bones stronger.

Similarly, there is a difference between exposing your immune system to a small dose of virus (say, via vaccine) and exposing it to a much larger dose. Double the dose results in much more than double the effect.

It is also important that the impact of the shock or stressor not cause total loss. If you are exposed to a viral dose large enough to kill you, your immune system doesn’t have a chance to get stronger.

Anti-fragility > Prediction

Anti-fragility occurs when systems, or things, have more upside than downside from shocks. When you have anti-fragile characteristics, you don’t need to predict when shocks will occur. You can sleep comfortably knowing that when they do occur, you will benefit.

Becoming anti-fragile

Let us recap what we know:

- What matters are outlier events

- Predicting outlier events is impossible

- Anti-fragility removes the need for predictions by putting us in a position to benefit from outlier events

The question, then, is how does one become anti-fragile?

Anti-fragility can be achieved with different tactics at different scales.

While I am still learning and updating my thinking, below is a list of some of the principles I have found useful in becoming anti-fragile, along with vignettes to help illustrate the points.

Principle #1: Redundancy

Anti-fragility is achieved through redundancy. Having extra capacity is a way to benefit from shocks. The difficulty is that redundancy seems wasteful if nothing unusual happens. The key is to be disciplined enough to build redundancy when you don’t need it for when you inevitably do.

Redundancy and money: Let me illustrate with a financial example. Having a sizable amount of your wealth in cash (say 10%) will make you anti-fragile. You will miss some short-term gain by not investing this money; however, when shocks or stressors eventually occur, you can be opportunistic, aggressive and have significant upside (e.g., buying assets at a big discount).

Redundancy removes the need for you to predict which outlier event will cause difficulties. External shocks cause value to flow towards a set of basic items. For example, in all of the following scenarios cash increases in value: war, market crashes, revolution, losing your job, pandemic, natural disaster, getting sick, etc. [4]

Redundancy and time: The same idea applies to time. Having the extra capacity to pursue interests, let your mind wander and explore opportunities that arise has more upside than scheduling every second of your time.

Redundancy and other systems: The redundancy principle applies to the system level as well. Hospitals, power grids, supply chains, traffic infrastructure, etc. are all systems that would benefit from having redundancy built in. Airplanes have incredible safety records due to the level of redundancy built in (e.g., they can fly their entire route on one engine and carry at least two hours of extra jet fuel). This principle should be extended to many other aspects of our lives.

Redundancy is often compared to having insurance. However, this comparison is not quite accurate. Insurance limits your downside but doesn’t provide upside (insurance is robust). Redundancy does.

Principle #2: Optionality

Having options leads to anti-fragility by allowing you to pivot to the most favorable outcome in an uncertain future.

New York rent: I live in New York, where rent is atrociously high. Had I been smarter, I would have moved into a rent-controlled apartment. Doing so would make me anti-fragile through optionality.

In a rent-controlled apartment, I have the option to stay for as long as I wish, but no obligation to do so. If I want to move, I easily can. Should rents increase dramatically, I am largely protected. However, should rents collapse, I can easily switch apartments and reduce my monthly expense.

Having this option creates asymmetry. I benefit from lower rents but am not impacted by higher rents. By having options, I don’t need to predict since I am prepared for any outcome in the rental market.

Options inherently have asymmetrical features. [5]

Principle #3: Post-traumatic growth

Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. – Victor Frankl

Admittedly, this next principle is somewhat trite, but it is perhaps the most important.

We are all familiar with the concept of post-traumatic stress, but less so with its lesser-known cousin, post-traumatic growth. Post-traumatic growth occurs when negative experiences spur positive change. [6]

It is not the same as being resilient. Resilience is robust—you survive shocks, but they don’t make you better. Post-traumatic growth is anti-fragile—shocks and stressors improve you.

Life will inevitably throw stressful events at us. How we react to these obstacles is our choice. By choosing to look for the good in the bad and to turn every obstacle into an opportunity, we can build anti-fragility.

This way we no longer need to predict since we are prepared.

Notes:

[1] It is interesting that sometimes you need to be right only once to make enough money and secure enough fame for the rest of your life. Asymmetrical bets, while unreliable, are worth pursuing.

[2] Yes, I did steal this example from Big Daddy.

[3] Sometimes, the status quo can actually make anti-fragile things weaker. For example, a lack of stressors or external shocks to muscles causes them to get weaker through atrophy. Another example is forest fires. A lack of forest fires (external shock) weakens forests through the accumulation of combustible materials. This results in forests being more prone to severe fires and higher probability of total loss.

[4] Having extra basic supplies (food, water, toiletries, energy, etc.) would have similar effects as having extra cash in many scenarios as well.

[5] Financial options and contracts have similar characteristics.

[6] Some fantastic articles on post-traumatic growth can be found here: HBR, Scientific American

I would recommend reading the works of Nassim Taleb, John Kenneth Galbraith and Howard Marks if you are interested in learning more.