On a walk earlier this summer I was struck by how many important decisions I have made over the last 12 months. I have made significant decisions across the major verticals of my life: career, relationships, investing and personal growth. After reflecting on this, I realized that the consequences of my decisions grow in a non-linear fashion each passing year. I also realized that I did not have an effective decision-making framework.

The quality of our decisions directly impacts the quality of our lives. As such, I have been focusing on learning how to make better decisions. This pursuit has led me to consider the concept of risk. What is risk? How should I think about taking risk? How do I protect myself from the risks of my decisions? I knew that having a strong understanding of risk would lead to better decisions in all aspects of life.

I began educating myself on risk, and by extension probability. I studied the works of Peter Bernstein to understand the history of risk and Howard Marks to understand risk from an investor’s paradigm. I realized that risk is not intuitively comprehensible but is involved in every decision we make.

What Is Risk?

Professor Elroy Dimson from the London Business School wrote the best definition of risk I have been:

“Risk means more things can happen than will happen”.

This quote captures the essence of risk because it highlights that risk only exists in the future. The source of risk is uncertainty in the future and the outcome of our decisions. If the future was knowable or predictable, then risk wouldn’t exist.

The Future Is Unknown

There are people who have strong conviction in our ability to predict the future. They point to the plethora of data we have, our ability to extrapolate from the past and use sophisticated models and computers to arrive at predictions. But I disagree – the future isn’t knowable.

The future is too complex for us to accurately predict. It is influenced by thousands of factors, such as the psyches of other humans, government policy, nature and weather, and randomness. Many of these factors we don’t fully understand, and some we might not even be aware of (these are called unknown unknows). The cause and effect relationships between these factors is far too weak for us to draw meaningful conclusions from.

Let’s look at one of the most common predictions as an example: economic forecasts of the U.S. Think about all the questions that surround this one prediction.

-

What will the unemployment rate be?

-

What will happen to commodity prices?

-

Will geo-political tensions lead to trade wars?

-

What will the rate of innovation be?

-

What will the Fed do? Will interest rates go up, down or stay constant?

-

What will the rate of population growth be? What about immigration?

-

Will productivity per person increase?

-

What political party will be elected? What policies will they implement?

The point is that no one can balance all these factors to reach an accurate prediction. Given the near-infinite number of variables that influence the future, the weakness of the linkages and the presence of randomness, it is my belief that the future cannot be predicted. Uncertainty still exists, and with it risk.

Risk & Uncertainty After The Fact

The most common way people try to understand the risk of their decisions is to look at the risk of past decisions. There is an innate sense that we can conquer and control risk by examining the past, searching for cause and effect relationships, spotting patterns of outcomes and drawing conclusions. However, risk can’t be determined even after the fact.

Why?

Because even after the fact, the connection between contributing influences and outcomes for complex decisions are far too imprecise and variable for the results to be dependable. Let’s look at an example.

Alexander the Great conquered much of his known world. He mapped out his battle strategy and it succeeded under the circumstances that presented themselves. He conquered parts of northern Africa, and western Asia, creating one of the largest empires the world had seen. It is widely believed that he never lost a battle.

But, were his victories and the circumstances that produced them a matter of skill or luck? Did he prudently plan for these circumstances or overlook them and get lucky? Were the opposing generals more prudent, systematic, and wise but happened to get unlucky due to randomness and lost? Who deserves to be remembered: Alexander the Great or the hypothetical wiser general? What specific cause and effect relationships can we draw? How confident are we in these conclusions?

While we can speculate about Alexander the Great’s skills as a general, some things in life are too complex for us to fully understand, and our degree of confidence in the cause and effect relationship is too low. Many things in life fall under this category: public policy outcomes, investments, economic growth, relationships, the success of a start-up, etc. There are too many variables for us to draw instructive cause and effect relationships from. The result is impacted by too many things outside of our control. The weakness of the connection between cause and effect makes the outcome uncertain and that uncertainty is the source of risk.

The point is that we can form expectations based on what has happened in the past, but we must take the events of the past with a grain of salt. While the past is not ambiguous, the definiteness of the past does not mean the process that created those outcomes is clear or dependable. Many things could have happened, and the fact that one did does not signal a lack of possible alternative outcomes. In other words, the history that occurred is only one that could have been. If you believe this, then the significance of history as a mechanism to understand and predict the future is limited. Peter Bernstein summarized it best with the following quote: “We like to rely on history to justify our forecasts of the long run, but history tells us over and over again that the unexpected and the unthinkable are the norm, not an anomaly. That is the real lesson of history.”

Dealing With Risk

Accepting that the future is unknowable puts us in a difficult position. We are supposed to make decisions which impact our lives in the future. Yet we don’t know what the future will be, and what risks we are exposed to. How then, do we make effective decisions in this environment? The answer lies in realizing that not being able to know the future does not mean we can’t prepare for it.

A Spectrum Of Possibilities

The future should be viewed as a range of possibilities, each with a respective likelihood of occurring – a probability distribution.

Having a sense of what is possible will allow us to better understand the risks and rewards of each scenario. The summation of this is the total risk and reward of the decision. Within this context, superior decision-makers, including investors, will have a better sense of the range and likelihood of each outcome and the risks they are exposed to.

Risk Has Consequences

Understanding the different possibilities and likelihood of outcomes is not sufficient to make effective decisions and manage risk. We need to consider the consequences.

In his memo, “Risk Revisited”, Howard Marks states that even though many things can happen, only one will. Said another way, there is a distinct difference between probability and outcome.

When making a decision, and exposing ourselves to risk, we need to be sure we can live with the consequences of the risk. Prudence requires us to consider the negative consequences of each scenario and judge whether this is a risk we can afford to take. This framework is called “expected value” decision-making.

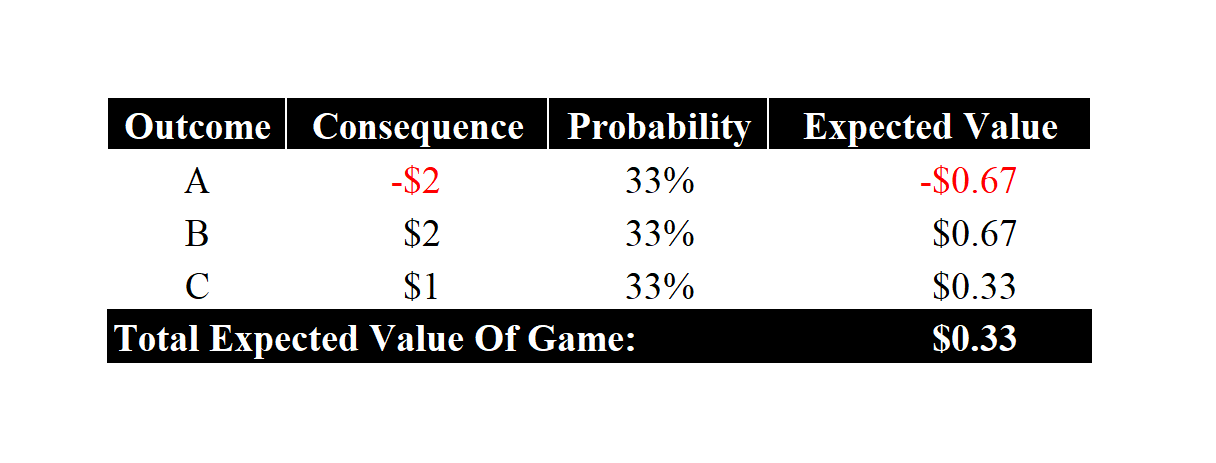

I will expand on this briefly. Let’s assume you are invited to play a game of dice with the following rules:

-

The dice has three sides: A, B, C, each with a 1/3 chance of coming up.

-

If you get side A you have to pay $2, side B results in you winning $2, and side C results in you winning $1.

The expected value would be the sum of all the probabilities of each outcome multiplied by the consequence of each outcome:

Assuming you can deal with the consequences of side A, this game has a positive expected value and thus is good risk to take.

Risk Is Messy

The difficulty with this framework is that it requires us to quantify consequences, and while this works well within the investment paradigm (where we can better quantify our consequences), the real world is messier than that. How do we quantify the risk of job loss, health loss, or reputational damage associated with a decision? The reality is that risk can’t be perfectly measured – it isn’t an objective quantifiable metric. Inherently, risk estimation will be subjective, imprecise and qualitative.

But understanding risk is essential to effective decision-making. Thinking through the probability distribution of outcomes and consequences of each decision we make allows us to ensure that risks we take are aligned with our personal circumstances, values, goals and beliefs.

In the end, effective risk-taking isn’t a science – it is an art. It is based on judgement. It is vague and messy. But as philosopher Carveth Read put it “It is better to be vaguely right than exactly wrong.”

Inspiration And Additional Readings: