I manage most of my assets personally and, as a result, I feel an ongoing responsibility to understand the world around me, as this enables me to make the best investment decisions I can.

Recently, I’ve been thinking about how to best allocate my portfolio given the current state of asset valuations, government debt, and general investor sentiment.

Through studying the works of Ken Galbraith, Howard Marks, Ray Dalio and other great investors, I have learned that the single most important variable in determining whether I should be aggressive or defensive with my portfolio strategy is the debt cycle. The ability to understand where we are in the debt cycle, and adjust our portfolios accordingly, is one of the hallmarks of great investors.

Before diving in, I want to emphasize that these are my views, and that different people have different perspectives. I hope that by sharing my views, I will encourage debate and advance our understanding together.

Cycles

At its core investing is making good decisions about the future. To do this well, investors need to form probability distributions of different outcomes to guide their actions.

But it is important to remember that even if we know the probabilities, we don’t necessarily know the outcome.

Howard Marks has a helpful analogy: successful investing is like choosing a lottery winner. The winner is determined by one ticket (outcome) being pulled from a bowl of tickets (many possible outcomes).

Superior investors have a better sense of what tickets are in the bowl, and thus, whether it is worth participating in the lottery. Said another way, great investors don’t know exactly what the future holds, but they have an above-average understanding of future tendencies and probabilities.

This brings us to cycles.

Understanding cycles helps us form a view of future probabilities. It helps us understand how many winning lottery tickets there are in the bowl.

Analyzing cycles is not a precise science. The goal is not to time the market; rather, it provides a directional sense of what has happened, and what might happen. Marks explains this elegantly:

The superior investor is attentive to cycles. He takes note of whether past patterns seem to be repeating, gains a sense for where we stand in the various cycles that matter, and knows those things have implications for his actions. This allows him to make helpful judgments about cycles and where we stand in them. Specifically: Are we close to the beginning of an upswing, or in the late stages? If a particular cycle has been rising for a while, has it gone so far that we’re now in dangerous territory? Is the market overheated (and overpriced), or is it frigid (and thus cheap) because of what’s been going on cyclically?

The most important cycle for investors to follow is the debt cycle.

Credit & Debt

Since we will use the terms “credit” and “debt” a lot, I will quickly define them.

Credit is the giving of buying power. When you take on credit, you exchange it for a promise to give it back; this is called debt.

Credit and debt, in and of themselves, are good things, and little credit and debt can be a bad thing. For example, if there is credit available to build roads, schools, and other essential infrastructure, that is a good thing. If the credit and debt are used to consume goods outside of one’s income level, that is a bad thing.

So, the overarching principle is that credit is desirable when the borrowed money is used productively to generate enough income to repay future debt obligations. If this occurs, good decisions have been made, and both the lender and borrower will benefit.

Debt Cycles

At the highest level, a debt cycle is the oscillation between credit and debt being easily available and being scarce. [1]

When credit is easily available, there is more money in the system. This leads to growth in GDP, asset prices, incomes, etc. and is called an economic expansion, or a “boom.” To prevent prices from growing indefinitely, central banks taper credit, which causes everything to shrink. This is called an economic contraction, or a “bust.” This dynamic has existed for as long as credit has been around, predating the Roman Empire. [2]

Debt cycles are nothing more than a logically driven series of events that recur in patterns. Whenever you borrow money, a debt cycle is created.

Let’s explore this in more detail.

A debt cycle has two distinct phases: (1) expansion; and (2) deflation.

Expansion:

Every debt cycle begins with widely available credit.

There is a famous line in In Fields of Dreams, “If you build it, they will come”. In the economy, if you offer cheap debt, people will borrow.

When debt is cheap, the threshold for its productive use is lower and skews more toward consumption. Since one person’s spending is another person’s income, higher consumption leads to higher incomes. Eventually, this leads to higher asset prices (stocks, bonds, real estate, crypto-assets, etc.) since there is more money chasing assets.

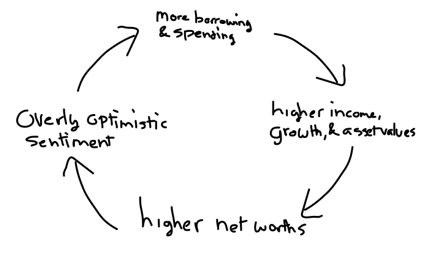

This has a positive self-reinforcing effect.

As incomes and asset prices inflate, people feel rich and start to take on even more debt.

Creditors look at the increased net worth of their debtors and feel comfortable giving them more debt. [3] This strengthens the feedback loop. Risk averseness diminishes, investor sentiment shifts toward optimism, and everyone thinks the good times will last forever. At this point debt is used more recklessly to fund consumption or projects with negative returns.

Deflation:

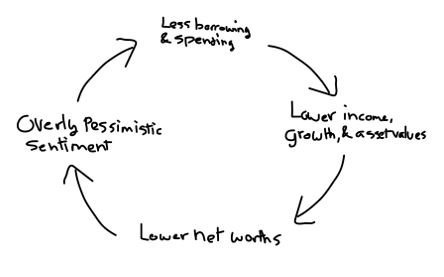

Eventually, to stop the upward cycle central banks taper credit, by making it more expensive. Making debt more expensive has two impacts: (1) people are less likely to take on new debt; and (2) existing debt becomes more expensive, which increases the risk of default and shifts spending away from consumption and investment to debt repayment. This triggers a negative spiral.

A lack of credit creates a liquidity problem. Investors and lenders become more critical of who they lend to. There is less money flowing around and consumption is reduced. Reduced consumption reduces income (remember that one person’s spending is another’s income). Lower incomes and lower asset prices mean lower net worths. Lenders, who were providing credit based on higher income and asset prices feel exposed and tighten credit even more. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle and the downward spiral continues.

Resetting the cycle:

To combat the downward spiral, central banks lower interest rates and make credit easily available again.

This marks the end of one cycle and the beginning of the next.

The Most Important Cycle

The slammed-shut phase of the credit cycle probably does more to make bargains available than any other single factor – Howard Marks

Why do I ascribe such importance to debt cycles?

Because credit, at least, impacts four important economic factors:

- Income Growth: Open credit markets are inflationary for wages. When credit is available, consumer spending is high. One person’s spending is another’s income, thus resulting in higher incomes and tighter labor markets.

- Net Worth / Asset Growth: Easily available credit results in more money chasing the same assets. This leads to higher asset prices and, as a result, higher net worths. Investors feel rich.

- Earnings / Company Growth: Companies need to fund investment in innovation and R&D to grow. Credit makes up the largest part of the capital pool. Cheap credit allows numerous projects to be funded, resulting in higher growth.

- Default Rates: Credit must be available for maturing debt to be refinanced. Entities, like companies, governments and consumers, often don’t pay off debts. Most of the time they roll them over. But if a company is unable to secure more debt at the time that its existing debt comes due, it may default and enter bankruptcy. [4]

When the credit markets are wide open, the cumulative effect of the above is overly optimistic investor sentiment. When incomes and net worths are high, growth rates attractive, and all businesses avoiding default, people think the music will never stop. As a result, the potential risk-reward spectrum of investing is at its least favorable.

But investor sentiment is also a cycle, shifting from overly euphoric to overly pessimistic. When we enter the deflationary stage of debt cycles, the inverse is true.

Making Good Decisions

The ultimate purpose of this essay is to enable you, the reader, to have a sense of where we stand in the debt cycle and take the appropriate action.

As such, I have outlined some typical signs of an open and cautious credit market.

Signs of an open credit market:

- Fear of missing out on profitable opportunities

- Reduced risk aversion, due diligence and skepticism

- Too much money chasing too few deals

- High debt levels and reduced ability to service debt expense

- High asset prices, low potential returns, high actual risk, and low perceived risk

Signs of a cautious credit market:

- Fear of losing money

- Heightened risk aversion and skepticism

- Shortage of capital everywhere

- Economic contractions and difficulty refinancing debt

- Low asset prices, high potential returns, low actual risk and excessive risk premiums

What does all this mean?

It means that one of the best ways to enjoy superior returns is to get the market on your side. Outcomes will never be under your control, but if you invest when the lottery tickets are biased toward favorable, you will have the wind at your back. Understanding cycles gives you a better chance of knowing when this is and positioning your portfolio accordingly. It helps you understand how many winning tickets are in the bowl and whether you should buy one.

The next logical question is where are we currently in the debt cycle and how should my portfolio be skewed toward the balance between aggressive and defensive?

At the time of writing this, I am leaning toward neutral-to-defensive. [5] When uncertainty is high, asset prices should be low, creating high potential returns that are compensatory. However, the combination of money printing and low interest rates has forced asset prices to be the opposite. While I don’t think prices are egregiously high, it is hard to find mouthwatering deals.

Notes, Inspirations & Additional Readings

Thanks to Kerri, Holden & Harry for their review and feedback.

[1] Ray Dalio explains that there are two debt cycles we should pay attention to: the short-term debt cycle and the long-term debt cycle. For the sake of this essay, I have ignored this distinction and the policy and political implications associated with them.

[2] In Debt: The first 5000 years David Graeber lays out the historical development of debt. The first recorded debt system was in the Sumer civilization around 3500 BC.

[3] What I find fascinating is that this seems rational. For example, if you buy a house for $50 in year 1 with $25 of debt your total debt-to-asset ratio would be 50%. The next year, your house is worth $75 on paper, so your debt-to-asset ratio is now 33%. Based on this, you take on more debt to get the ratio back to 50%, resulting in ~$38 of debt. But what if your home price drops back to $50? Then your debt-to-asset would be 76%.

The point here is that the amount of credit one has available is often based on asset value, which is a variable number.

[4] Many corporate assets, such as buildings and machinery, are long-term in nature. But they are often financed with short-term debt because the cost of borrowing is lower relative to long-term debt. This mismatch is what drives the default risk that is associated with credit markets drying up.

[5] It is outside the scope of this article for me to go into great details as to why. If you want to have a deeper conversation on this, please reach out.