For years, skydiving was on my bucket list. Yet, year after year, I failed to cross it off; I always had an excuse.

Finally, in the summer of 2020, I built up enough courage to do it and it was an exhilarating experience. The sensation of free-falling is one that I’d never experienced before. Because of all the stimuli, skydivers experience sensory overload during the jump and then a euphoric high afterward.

A friend asked what I’d learned from skydiving. It was an interesting question because initially, I thought I hadn’t learned anything. But after giving it more thought, I realized that skydiving helped me understand two decision-making principles I had learned:

1) The importance of searching for reality

2) Solving for incentives

Perception ≠ Reality

Jumping out of a plane and falling at a terminal velocity of 120 miles per hour seems dangerous; it seems as if you’re gambling with your life. But perception does not equal reality.

According to the Oxford Dictionary, perception is defined as follows:

“An idea, a belief or an image you have as a result of how you see or understand something.”

And here is the dictionary definition of reality:

“The true situation and the problems that actually exist in life, in contrast to how you would like life to be.”

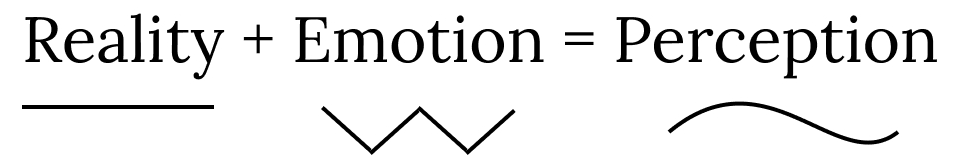

The key difference between perception and reality is emotion.

Reality is void of emotions or judgements. Situations or facts are not labelled as good, bad, happy, or sad – they just happen. It is our perception that causes us to label reality.

Think of the relationship this way. Perception is the lens through which we view reality. Our perception is impacted by numerous variables: how we interpret information, our genetic predisposition, our education, our environment, our experiences, our current emotional state, our cognitive biases, and so on.

How Much Is A Flower Worth?

“The critical feature of the speculative episode is that, after a time, the market loses touch with reality.” – John Kenneth Galbraith

Understanding this allows you to identify situations in which perception deviates from reality. When this happens, opportunity and asymmetrical payoffs are near.

Let’s examine this within the world of public markets. When a person’s perception deviates from reality, the quality of their decisions decreases. They stop looking at things objectively. They don’t consider the other side, and they ignore any facts that disprove their beliefs.

When perception and reality deviate, you end up with irrational markets; speculative episodes; and, accordingly, opportunity. My favorite historical example of this is referred to as “Tulip Mania.”

In the 17th century, Holland had the first modern stock market, and is where we find the first modern example of a “bubble.” The most fascinating thing about the first market bubble – and why it is my favorite – is that the item experiencing speculation was a tulip.

The tulip grows wild to the Mediterranean countries. In 1562, the flower was introduced to Holland where its beauty quickly caused it to become a status symbol. Displaying the flower – especially esoteric varieties – became incredibly popular and a sign of your wealth and success. The rarer the tulip, the more expensive it was. Prices increased day by day, which fueled additional cycles of price appreciation.

By 1636, Holland was engulfed in a rush to invest in tulips. No price was too high. A tulip could be exchanged for a horse, then two horses, and then for a carriage and two horses. People began converting their property into cash and leveraging their assets to invest in tulips. Greed took over, and no one stopped to asked, “How much is a flower really worth?”

In 1637 the party ended. Prices had reached the point where people’s euphoric state could no longer justify them. The crowd’s perception and reality began to reconnect. Greed and envy were replaced with an understanding of what had happened, and then fear and panic. Tulip prices dropped, fortunes were lost, lives were ruined, and Holland entered a deep depression.

Disconnects Are Everywhere.

A clear understanding of reality allows for avoidance of speculative episodes like Tulip Mania. If you can keep your ability to control your perceptions and find reality, you can take advantage of these situations.

This also applies to life outside of investing – for example, skydiving.

Skydiving is incredibly safe. According to the United States Parachute Association, in 2019, only 15 fatalities were recorded out of 3.3 million jumps. Tandem skydiving had an even better safety record, with one student fatality per 500,000 jumps. That is a 0.0002% chance of death. You are more likely to die from being struck by lightening (1 in 180,746) or stung by a bee (1 in 53,989).

Yet, people still view skydiving as dangerous.

Jumping out of a plane does seem dangerous. It triggers emotions, which generate a disconnect between perception and reality. Statistics and evidence demonstrating its safety are ignored.

As a result, most people avoid skydiving, concluding that they are not risk-takers or adventurous. People who maintain a view of reality can take advantage of this. They can experience the thrill of skydiving, and the boost in social status associated with being an adventurous risk-taker, but without the actual risk.

The Principal-Agent Problem

Before I did the jump, friends would ask whether I was scared to skydive. My answer was no.

This wasn’t because I was brave or had confidence in my ability to solve any problems that might occur mid-fall. It was because tandem skydiving is one of the best solves to the principal-agent problem I had seen.

I was first exposed to the concept of the principal-agent problem when I was in law school. Simply put, the problem occurs when one person or entity (the “agent”) is able to make decisions that impact another person or entity (the “principal”). The core of the issue is incentives: the agent is motivated to act in their own best interest, which may be at odds with the principal’s.

Think of a start-up founder and their employees. The principal is the founder; the employees are the agents. The incentives of the principal are different from those of the agents (largely due to how ownership of the business is divided). The founder wants what is best for the business’s long-term success, while the agents want what is best for them (i.e., individual economic gain, short-cuts that produce a better quality of life, hiding problems to avoid reprimand, etc.). These differing incentives create sub-optimal outcomes for principals.

Solve For Incentives

“Never, ever, think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives.” – Charlie Munger

If you want to impact human behaviour, solve for incentives. The desired behaviour you want will be most influenced by the incentive structure of the system within which you operate. As an investor or founder, you will want to spend a lot of time thinking about solving this problem. How do you align your interests as the principal with those of the agent? How do you create incentives to achieve the desired behaviour?

Tandem skydiving is an amazing example of the alignment of interests between principal (customer) and agent (instructor).

Human self-preservation incentives are strong. The desire to avoid death is the most powerful incentive there is. When I was attached to my jump instructor, I found comfort in knowing that our incentives were perfectly aligned. My survival guaranteed his survival.

In investing, entrepreneurship, or life in general, look for situations that have solved the principal-agent problem. That way you can jump without fear.

Notes, Inspirations & Additional Readings:

-

A Short History of Financial Euphoria By John Kenneth Galbraith

-

Thanks to Charlotte, Kerri and Chad for their review and feedback.